on total honesty (10/10)

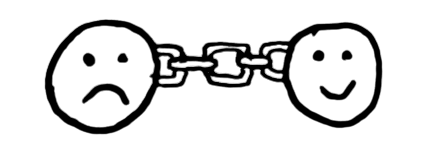

Diogenes of Sinope, for lack of a better term, was a dichotomy of a man.

He was extremely controversial: Exiled for debasement of currency. Called out for public indecency many, many times (“if only it were as easy to relieve hunger by rubbing one’s stomach…”, he would say). Captured by pirates and sold into slavery, for he “needed a master.”

Yet, at the same time, he was extremely simple. Slept in a giant ceramic jar. Begged for a living, eating whatever he could find with no regard for pleasure.

There’s a long-told story where Diogenes walks around the marketplace, barely clothed, holding up a bright-shining lamp in the heat of the daytime. When asked why he was doing something so blatantly absurd, he would persistently respond:

"I am looking for a [honest] man."

It’s not that Diogenes was literally looking for an honest man, someone to help him live a simple and virtuous life. He was looking for quite the opposite: dishonest, vicious men who would look into the lamp and realize they were contributing to the injustice and material fetishness that rampaged Greece.

We like to think that we’re honest people. That we can be straightforward, open, talkative enough to create a sense of transparency in our lives.

That’s what we’ve been taught, after all. "I admire your honesty," a character in one of Aesop’s fables says, "and as a reward you may have all three axes, the gold and the silver as well as your own." Honesty is the best policy, and the best policy reaps the highest reward.

And in a world where the highest reward could mean a variety of different things, people capitalize on our value for honesty to reap the rewards for themselves. The man is honest, and thus heals his relationship with his partner. The politician is honest, and thus garners more votes.

Consider the words of Albert Camus: "If pimps and thieves were invariably sentenced, all decent people would get to thinking they themselves were constantly innocent."

Here lies the crux of our dilemma. In linking honesty with the social or economic rewards that accompany it, we create a world in which the truth is incentivized, in which we believe people ought to get rewarded for doing the right thing.

Doesn’t sound too bad, huh?

Yet, in doing such, honesty is no longer what we were taught it was. More a carefully-crafted display of vulnerability than one of direct openness, the honesty we claim to know and recognize often serves our own interests more than it does the truth. We’re not really fixing anything, or building the virtues we praise–we’re assuaging our own guilt.

Total honesty as we know it, it seems, is less a catalyst for change and more a mirror reflecting our collective inertia. For in a world where every thought is spoken, every action scrutinized under the unforgiving light of absolute truth, what room is left for the messy, contradictory process of living?

Diogenes knew this. His lamp wasn't seeking an honest man - it was exposing the folly of such a quest. In the harsh glare of total honesty, we might feel better in the moment, but does that compel us to action, to empathy, to the values of community?

Even Diogenes knew when to extinguish his lamp and retreat to the shadows of his ceramic jar. There’s only so far total honesty can bring us.