on rigidity and building a system (redux) (7/4)

On July 9, 1776, thousands of Continental soldiers would march through lower Manhattan to hear perhaps the most highly-anticipated speech in the history of their country: the Continental Congress was calling for independence for the United Colonies of North America.

It was one of the greatest experiments in political history – a ragtag collection of colonies uniting to overthrow one of the most powerful imperialist nations in the world.

And some twenty years later, President Washington, upon the end of his term, would speak on such a historically improbable feat, and the political foundations of the nation he sought to create. “The basis of our political systems,” he claimed, “ is the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government.”

Upon the failure of the Articles of Confederation, this was all he could ask for. Nothing more, nothing less.

Around a month ago, I wrote this about systems and their purpose in one’s life:

“A good system should be your motivator, your teammate, and your coach all in one. A good system should keep undermining your goals, your beliefs, your predispositions, and push you even further than you thought possible.”

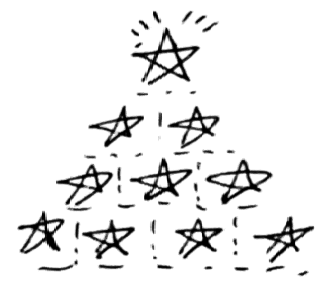

Weeks later, I continue to affirm what I said. Yet, at the same time, a system is not meant to be composed of rigid qualifications. A system, in the most strict sense of the term, is not solely defined by the qualifications that I’ve listed above. A system is undefinable – in that its success cannot be brought out solely by its component parts.

Washington’s political system was young, and people needed a definition to survive. Without something to look up to, something to strive for, there were no principles upon which the nation could survive.

Some 250-ish years later, there are some who will agree with Washington’s system – that there is nothing more essential to this country than the security of the Constitution. But there are still some who will inevitably disagree – that traditional political systems are hurting more than helping.

“The world needs open hearts and open minds,” philosopher Bertrand Russell would write, “and it is not through rigid systems, whether old or new, that these can be delivered.”

If there’s been one word to define the modern political cycle, it’s been rigidity. An inability to compromise. A lack of composure. An erosion of the foundation that threatens us all.

It is not through rigidity in which we can derive our religious beliefs. It is not through rigidity in which we can derive our communities. It is not through rigidity in which we can derive our morals.

And it is not through rigidity in which our political system can survive.