on Ben Shapiro's hierarchy of masculinity (8/29)

The debate surrounding masculinity, and subsequently what it means to be a “man”, has grown exponentially in the past few weeks, thanks to polar-opposite male leaders in the political news cycle Tim Walz and J.D. Vance.

The definition of “man” itself has only been discussed by hyper-conservatives concerned with labels, yet the arguments have centered around masculinity itself, and its role in society. And since I have not published a piece on such a lengthy topic yet, being a man presumably performing a role in society, I’ve organized some thoughts on this issue below.

In an article he wrote for Newsweek, social media politician Ben Shapiro argues that we need fathers to teach boys manliness, that we can’t disparage masculinity as a construct to be thrown away for the sake of emotional sensitivity. To argue for the equal treatment and inclusion of alternative families, such as LGBTQIA+ couples or adoptive single parents, is unethical according to Shapiro, due to the fact that it “leaves men without a mission.”

Here’s one passage in particular that struck me:

“The #MeToo movement says men must be taught not to rape. But no good man has ever been taught not to rape. Good men are taught, generally by a male authority figure, to affirmatively stand up for women, to prevent harm. It's not enough to teach boys "not to rape." Boys must be taught to fight rapists….

But men are still different from women, and they know it. Deprived of purpose, too many men turn to empty substitutes for true manliness: a macho culture that prizes sexual conquest or physical strength, for example. Men become bros rather than husbands and fathers. Liberated from responsibility, many men become users—after all, women and men are exactly the same, and to suggest that men protect women is a form of patriarchalism. So the cycle perpetuates. Without fathers, these men's sons all too often grow up to become their absent dads.”

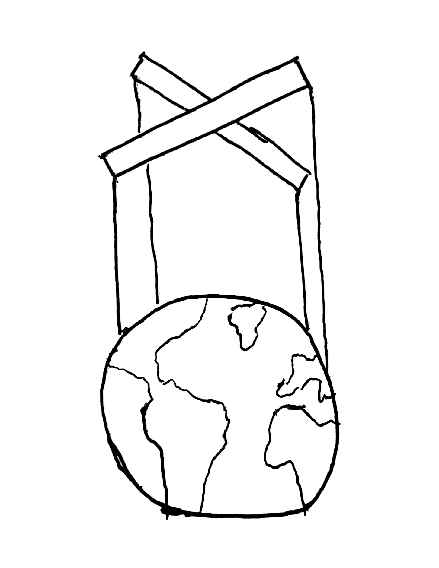

As with many, I was tempted to stop reading at the point in which he claims “but no good man has ever been taught not to rape.” But, in making the claims as he does he, Shapiro makes an interesting, if not heavily controversial point, when combined with what we discussed above, forms a hierarchy of masculinity, shaped as such:

(Presumably) heterosexual men, in conforming heterosexual relationships

Women

“Bros” enveloped in masculinity’s macho culture

Families differentiating from heterosexuality (LGBTQIA+, single adoptive, etc.)

The glue for Shapiro’s argument, and for this hierarchy, is the values that he attributes to masculinity: strength, a commitment to safety, and leadership being the big three. (Brett McKay, another influential masculinity blogger, even claims that “strength forms the nucleus of manliness.” And you still think men don’t care about height/strength/physical features?)

Yet, there’s a severely significant value that Shapiro ignores throughout the article, one which essentially negates his entire argument: the community surrounding these relationships. The perspective in which Shapiro forms his argument is one in which men are the focal point, and woman, along with other identities, are byproducts of men’s actions: a good relationship is indicative of a well-raised man, well-raised children are indicative of a “masculine” father, etc.

Neglecting the community in which men are shaped, along with other players in such a community, is harmful in many ways. The most obvious is that it categorizes members of a group solely by their identity/gender/sexual orientation rather than by the values under which they stand by (oftentimes which we learn we share with one another, but cannot overcome the categorical boundary to share said values). Another harmful implication of this attitude, however, is that it holds societal factors accountable for masculine mistakes or actions. The “macho culture” Shapiro derives above is not a result of men’s actions, but rather the absence of women from their lives that forces them into such a state.

Masculinity cannot simultaneously sit at the top of a hierarchy and remain unaccountable for actions. It simultaneously cannot preach for a return to its values–strength, safety, and leadership–when all of its proponents are men lacking precisely those traits.

The paradox of Shapiro's argument, and indeed much of the contemporary discourse on masculinity, lies in its simultaneous elevation and absolution of men. It demands that masculinity be revered as the pinnacle of societal virtue, yet refuses to hold it accountable for its shortcomings, a contradiction which exposes a fundamental weakness in the traditionalist view of gender roles: it cannot withstand the complexities of modern society.

This paradox reveals more than just flawed logic—it exposes a desperate attempt to cling to power in a world that's outgrown such rigid definitions. True strength isn't found in dominating a hierarchy, but in dismantling it.

And thus, in the end, Shapiro's argument doesn't defend masculinity—it betrays its fundamental insecurity. And in doing so, it unwittingly makes the strongest case yet for why we need to radically redefine what it means to be a man in the modern world.