on demagogues and consumption (7/25)

Running through media, political speeches, academia and personal conversations alike this year is the topic of misinformation. The idea that in a society of mass consumption, we’re subjects of a campaign to swing our opinions and biases in a different direction.

“Against our will, our souls are cut off from truth,” Marcus Aurelius writes in Meditations, dating this conflict centuries behind us. Socrates was put to death for corrupting the youth. Jesus was antagonized by the Pharisees for his religious sway.

It’s easy to think of these issues as grand, overarching issues that are too blunt to overlook. Typically, when one thinks of misleading information, of “propaganda”, for lack of a better term, they’re left thinking of a sprawling, maniacal campaign used by Hitler or Soviets or another political enemy of the United States.

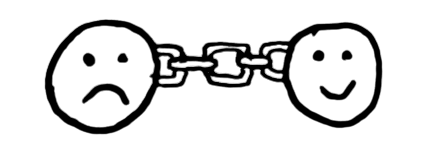

More powerful, however, is the use of manipulation to increase dependency on the words at hand.

It’s a practice that every writer is familiar with, and one which your favorite writer most likely uses in their work.* Lulling the reader into a rhythm of prose, a dependency in which their conscious opinions while reading become synonymous with those of the writer.

For when Marx says that “products of the human brain” appear as autonomous beings, we identify those autonomous thoughts as our own, not as the product of others. And with the repetition, with the dependency on the ideas that we subtly deem as our own, we give them credibility as well.

“Things possess an infinite quality when moving in a circle which they lack when advancing in a straight line,” Galiani once said on commodities, yet almost fittingly more on information. The more information gets circulated and engrained, the more definite it becomes relative to the rest.

And thus, much contrary to popular opinion, the battle against misinformation or propaganda or “fake news” is not fought on a national scale, one in which we are to spite the cable networks we grew up with.

It’s personal. It’s the “autonomous” thoughts we build surrounding our consumption. It’s the quiet moments of reflection in which we are to challenge our own assumptions.

It may be an age, a year of information warfare – but not in the way that you think. The most dangerous propagandist is not the demagogue on the screen.

*I neither confirm nor deny.